The Orchestra of the Reading Rope Harmony

Posted by Brainspring on 24th Mar 2021

Where was Scarborough’s Reading Rope back when I started teaching? After going through college as an education major in the 90s, the complexities of reading, including how one learns to read and comprehend text, were still baffling to me.

I began my teaching career in 1995, where I taught high school English and later moved to grade 8 language arts. For the most part, I thought I could tell whether my students were skilled readers or not. If they did struggle, the culprit was either fluency or comprehension, or so I thought.

During this time in education, formal assessments used to evaluate students for reading struggles or potential reading disabilities were not available unless one was an educational psychologist. And even then, the word dyslexia seemed foreign. Instead, our assessments were either informal, based on observations, or student work. So, could I say that my students were all skilled readers? Could I prove this with data supported by evidence-based assessments?

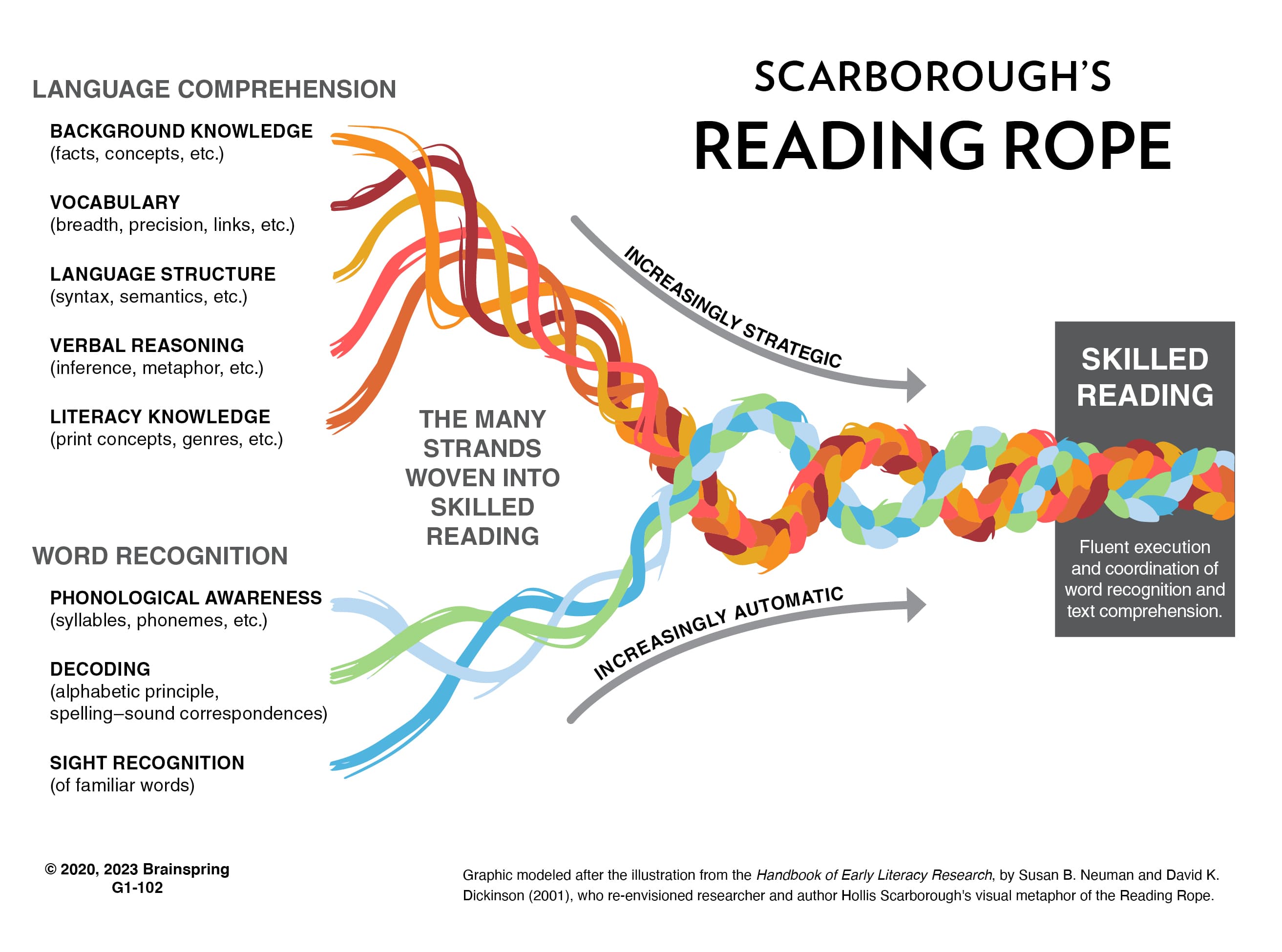

But then something happened: Scarborough’s Reading Rope had lassoed the world of education by visually organizing the complexities of reading.

History of Scarborough’s Reading Rope

This year marks the 20th anniversary of when Scarborough’s Reading Rope was first published in the Handbook of Early Literacy Research written by Susan B. Neuman and David K. Dickinson. Since 1992, even before this Reading Rope was published, Dr. Hollis Scarborough, the creator, used this visual metaphor to explain to educators the reading processes that needed to co-occur when becoming a proficient reader.

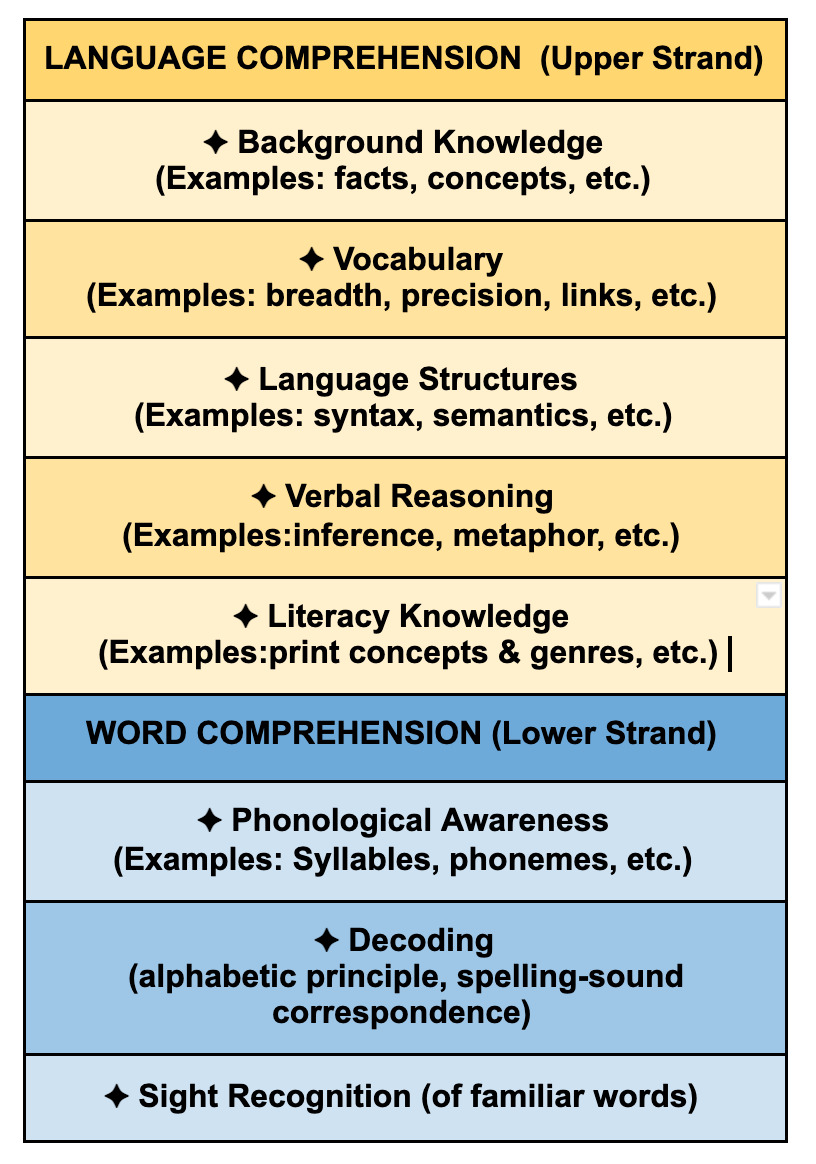

Scarborough’s Rope is divided into two strands. The lower strand, Word Recognition, consists of phonological awareness, decoding, and word recognition; when these skills are frequently practiced, automaticity, accuracy, and fluency are achieved. Meanwhile, the upper strand, Language Comprehension, is developing and integrating background knowledge, vocabulary, language structures, verbal reasoning, and literacy knowledge. Together, with a great deal of practice time and explicit instruction, these two strands are woven into the outcome: a skilled reader who can fully comprehend a myriad of texts.

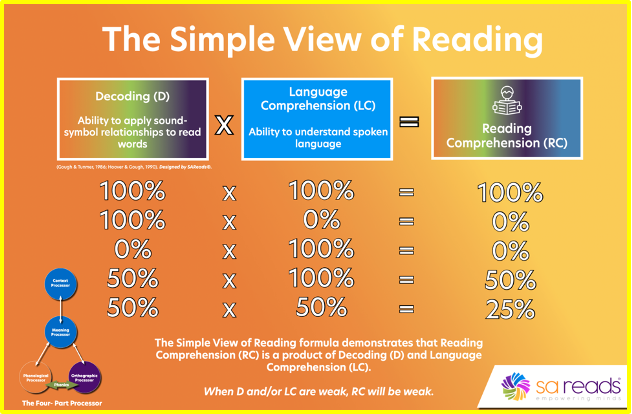

Though the Simple View of Reading (Gough & Tunmer, 1986) had concluded that if either oral language comprehension and/or word reading/decoding was missing, then reading comprehension could not be achieved. On the other hand, Scarborough’s Rope (2001) expands this fundamental view of reading and lists explicitly what a proficient reader needs.

The Meaning Behind the Rope

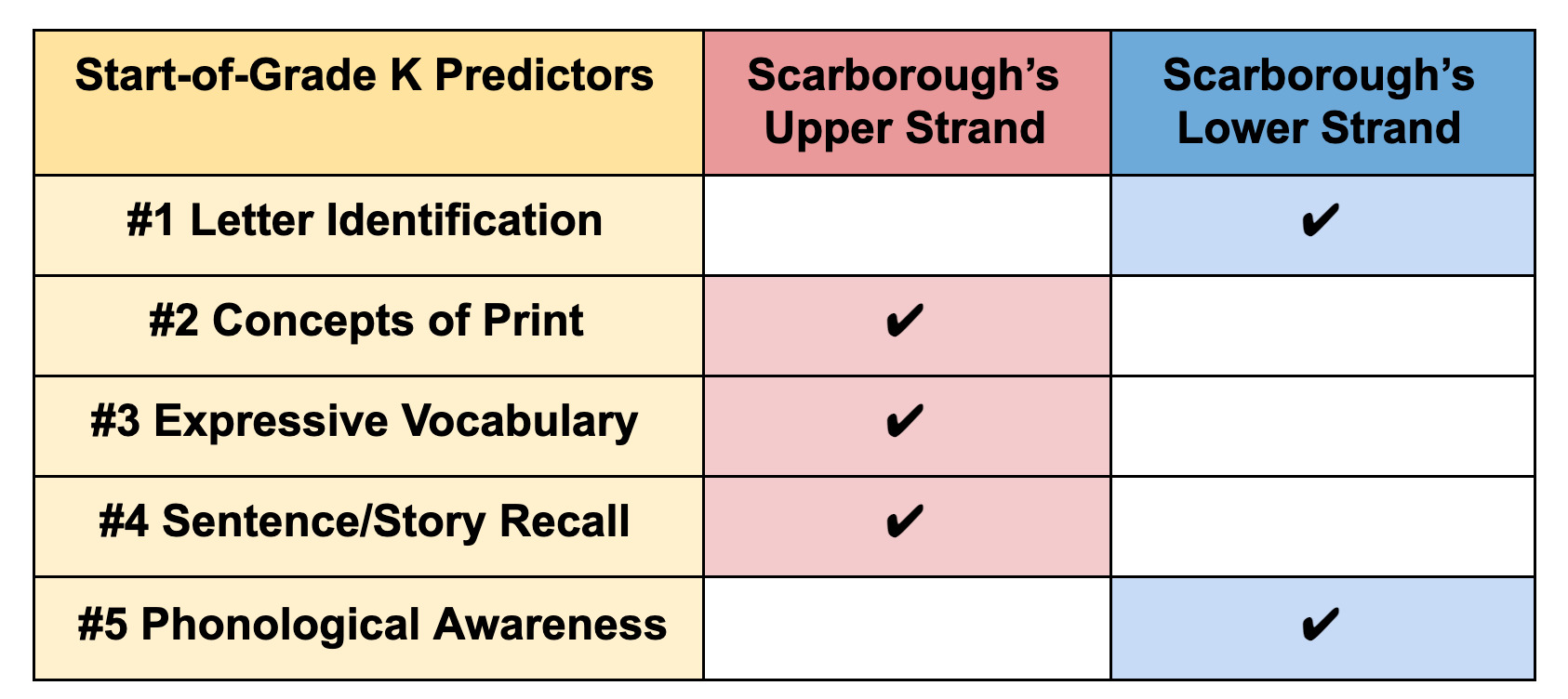

In 2018, Dr. Hollis Scarborough completed a meta-analysis of 61 studies and identified that the top five “start-of-grade K” predictors, indicating reading proficiency in grade 2, were found in either the upper or lower strands of the Reading Rope.

My Personal Connection

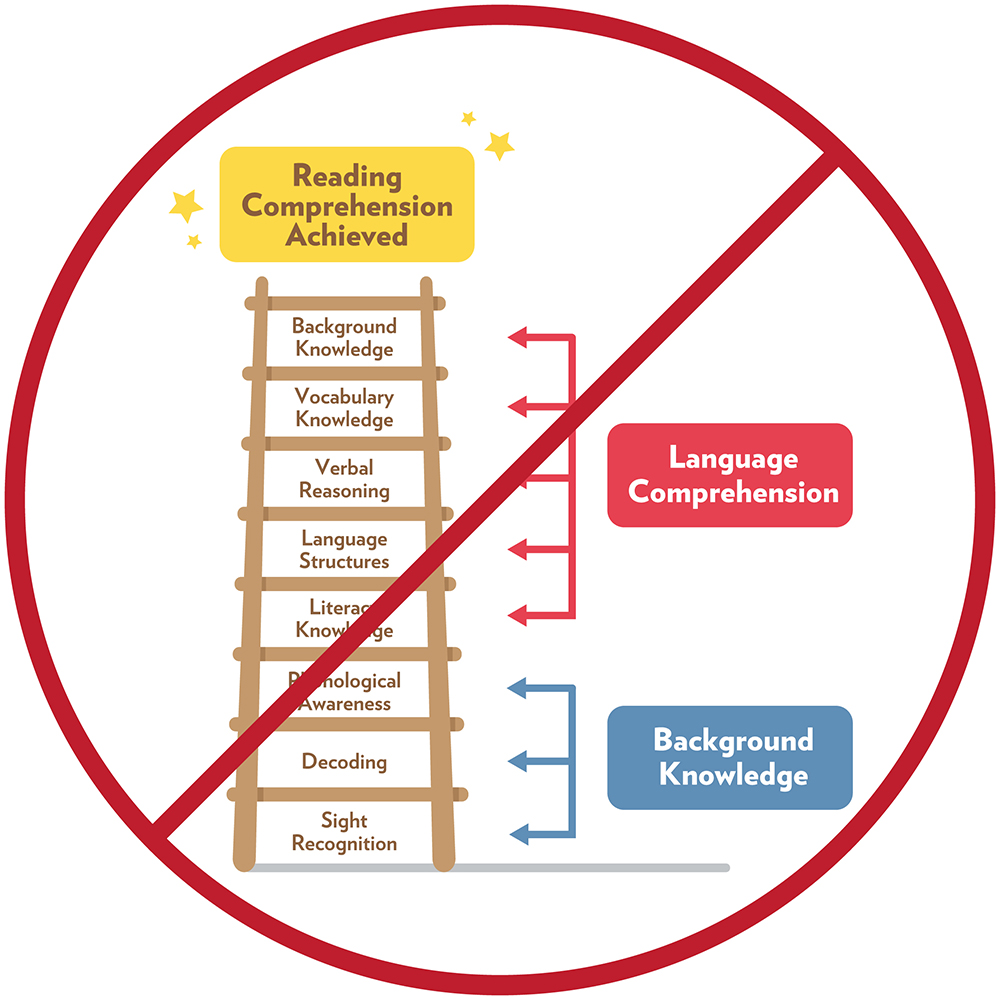

Over the years, I have worked with my share of literacy curriculums. And although there is no perfect “teach my child to read” curriculum, many of these seemed to address either the Language Comprehension strand or the Word Recognition one. During my secondary literacy experiences, there was more focus on Language Comprehension (upper strand). Then, at the elementary level, the “basics” found in Word Recognition (lower strand) were taught.

My literacy perspective, along with many others in the education field, was incorrect as the above strands should not be seen as the rungs of a ladder where one climbs up or “masters” one step at a time. Since learning to read is not natural and takes years of practice, the above skills should not be taught in isolation or as separate entities. Instead, these individual strands, found in Scarborough’s Rope, need to be taught concurrently.

Education in the Present

We now have an RTI process and curriculum-based measures (CBM) based on the science of reading research such as Dibels and Aimsweb. These measures align with the top five “start-of-grade K” predictors found in Scarborough’s Reading Rope and help educators be proactive by identifying at-risk readers very early. To close the gap of a potential “at-risk” reader, teachers and specialists should choose the correct intervention based on formal assessments, CBM’s, and teacher observations.

In conclusion, the more I study reading, the more I am convinced that learning to read is very similar to an orchestra successfully playing a music composition. Just as each instrument has a part to play in a song, reading also has its own set of tools that need to play together in harmony.

Resources

AIM Institute for Learning & Research: The Animated Reading Rope: https://institute.aimpa.org/resources/readingrope

IDA: Scarborough’s Reading Rope: A Groundbreaking Infographic

Science of Teaching Reading: http://www.literacysanantonio.com/science-of-reading

Part 1: The Science of Reading Basics: The Reading Brain https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dWWCmuAEBB4

Part 2: The Science of Reading Basics: The Simple View of Reading https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QtDEMHMRd8E

Part 3: The Science of Reading Basics: Reading Brain: Scarborough’s Reading Rope https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JR7GbAHntQ4

Pattan: Celebrating 20 Years of Scarborough’s Rope (Video)

https://institute.aimpa.org/resources/readingrope

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dWWCmuAEBB4

Written by Jennifer L. Padgett, M. Ed.

Jennifer is a Structured Literacy Specialist, K-12 in Mexico, Maine.

Brainspring has proudly supported the educational community for more than 25 years.

Our Educator Academy provides educators in grades K-12 with comprehensive MSL Professional Development courses. Learn more about our in-person and online professional development.

The Learning Centers support students through one-on-one, multisensory tutoring sessions. Learn more about our in-person (available in Southeast Michigan) and nationwide online tutoring.