Literacy as a Public Health Investment: A Survey Examination

Posted by Athena Lewandowski on 20th May 2025

A growing body of research shows that literacy rates predict later population health levels. Individuals with high literacy can better understand medical information, navigate our healthcare systems, and make informed health and medicine decisions than those who struggle with reading (Coughlin et al., 2020). Literate individuals are generally more prepared to make choices which lead to healthier, longer lives than illiterate individuals. The “Mississippi Miracle” is an incredible real-life example of how boosting literacy rates boosts long-term health outcomes. This phenomenon is discussed in detail below to highlight the interlinking nature of literacy and public health and the importance of early childhood reading education. Brainspring provides a public health investment into childhood literacy that is markedly beneficial in promoting long-term public health outcomes.

The Link Between Literacy and Health Outcomes

The ability to understand and benefit from health information is called health literacy (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2025). An individual’s health literacy is directly influenced by that person’s basic reading skills which are typically developed in early elementary school (World Health Organization, 2024). Low health literacy is associated with higher rates of hospitalization, poorer management of and outcomes from chronic diseases, lower rates of usage of preventative services, and overall increased rates of mortality and at younger ages (Coughlin et al., 2020).

Individuals with low literacy are more likely to struggle with following medication instructions, understanding hospital discharge and care instructions, and accessing preventative care services (Shahid et al., 2022). Communities with higher literacy rates consistently have better population health markers (O'Neill & Geisler, 2023). These communities typically have lower rates of smoking, obesity, and chronic diseases such as diabetes or heart disease (Tolonen et al., 2021).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) (n. d.), communities with higher literacy rates are more likely to engage positively with public health campaigns. Literate community members access appropriate preventative medical care, join exercise initiatives, and follow healthy eating initiatives at higher rates than communities with low literacy because those with strong literacy can better understand the information presented by public health leaders (World Health Organization, n.d.). Improving literacy rates is not just about education, but it is also a critical factor in improving public health.

Early Intervention: Why Childhood Literacy Matters

The foundation for health literacy is laid in childhood, typically through elementary school reading education. Research consistently shows that students who cannot read proficiently by the end of third grade are four times more likely to drop out of school before graduating than those who can read proficiently at grade level (DellaVecchia, 2020). Children who drop out of school tend to have poorer long-term health outcomes (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, n.d.).

Reading success in fourth grade is considered a benchmark because it marks the transition from learning to read to reading to learn (Bozkuş, 2023). Fourth grade reading proficiency rates can be used across the United States as an early predictor of community health. In Mississippi, for example, early reading intervention is recognized as one of the most effective public health initiatives (Javorsky et al., 2024).

The “Mississippi Miracle”: A Case Study

The “Mississippi Miracle” refers to the educational phenomenon which has occurred across the state of Mississippi in the past fifteen years. In 2013, Mississippi ranked 49th out of the

50 United States in fourth-grade reading rates on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) (National Assessment of Educational Progress, n.d.-b). However, in 2022, Mississippi’s fourth-grade reading scores on the NAEP exceeded the national average and shot the state into ranking 21st (National Assessment of Educational Progress, n.d.-b).

This incredible shift in Mississippi’s childhood literacy rates, in under a decade, was no coincidence. In 2013, in response to its abysmal literacy ranking on the NAEP, Mississippi policymakers implemented a massive set of research-based reading reforms (Javorsky et al., 2024). These included high-quality teacher training focused on the science of reading, implementation of statewide literacy coaching, and use of research-based reading strategies (Javorsky et al., 2024). Brainspring was part of the teacher-training initiative.

As illustrated by the 2022 NAEP results, the impact of these new reading intervention policies and trainings were significant. Additionally, as Mississippi student literacy rates soar, the impact of these initiatives will affect future public health outcomes. It is still too early to measure the full public health impact of the Mississippi reading reforms. However, existing evidence, as discussed in brief above, indicates that this investment in literacy will create healthier, more resilient populations over the coming decades.

Literacy is a Public Health Investment

The “Mississippi Miracle” highlights an important public health strategy - improving literacy. According to the 2022 NAEP (n.d.-a), over ⅔ of our nation’s fourth grade students do not read with proficiency. We must begin to view literacy as an urgent public health priority in order to protect our long-term public health interests. Shulman et al., (2024) stated that children who receive evidence-based reading intervention, especially during elementary school, are more likely to maintain better health. They are less likely to engage in risky health behaviors, more likely to access preventative care, and better equipped to manage chronic health conditions (Shulman et al., 2024).

Brainspring: Building Stronger Readers and a Healthier Future

Brainspring offers a proven solution to the childhood literacy crisis. By providing educators across the United States with evidence-based, structured literacy training that is grounded in the science of reading, Brainspring enables teachers to shrink the literacy gap. Brainspring’s accredited professional development programs, which are Orton-Gillingham based structured literacy, provide teachers with research-based early reading and intervention strategies for individual, small group, and classroom instruction.

Across the country, in hundreds of schools and districts where Brainspring’s teachings have been implemented, teachers report higher confidence in their instruction and deeper understanding of how students learn to read. Archival pre- and post-course survey data were collected from 310 educators who participated in Brainspring’s Phonics First® and Structures® courses between January 1, 2025, and March 31, 2025.

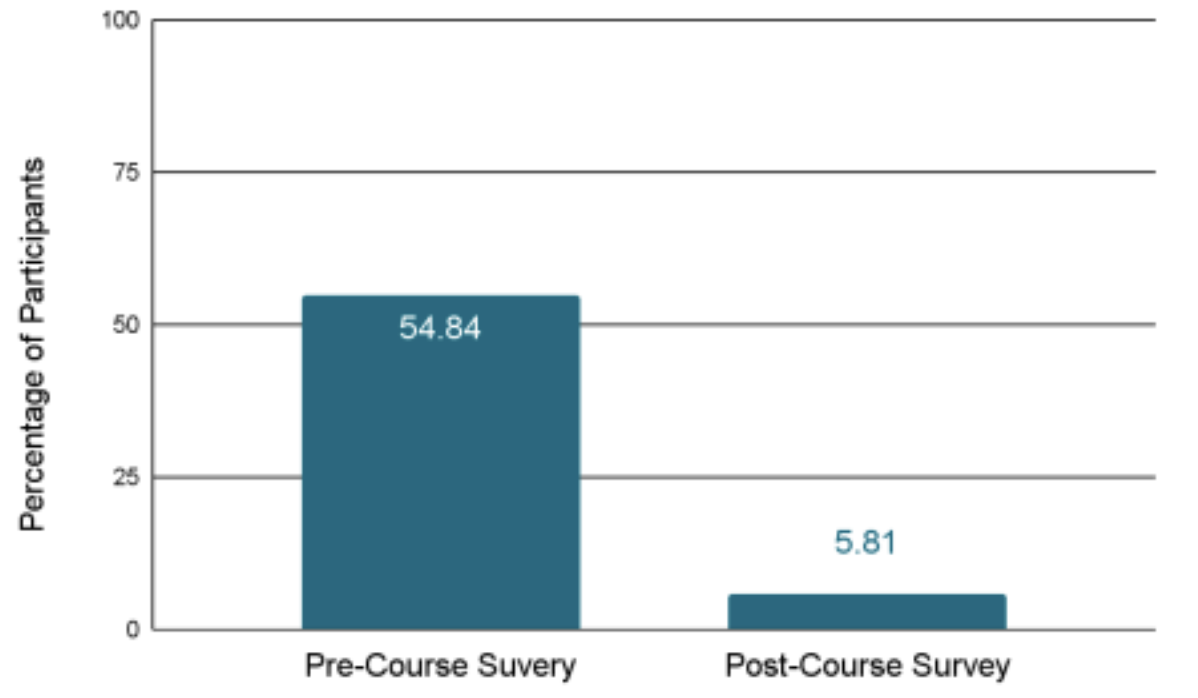

Using a Likert scale, pre- and post-course surveys asked educators to rank their confidence in implementing the Orton-Gillingham structured literacy approach. Results of the data analysis show that before taking a Brainspring professional development course, 54.84% of teachers were not at all confident in their ability to implement the Orton-Gillingham structured literacy approach with students. After taking a Brainspring professional development course, this percentage decreased to 5.81% (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Percentage of participants who responded “not confident.”

Note. The percentage difference of educators responding “not confident” on the Likert scale changed by 161.68%.

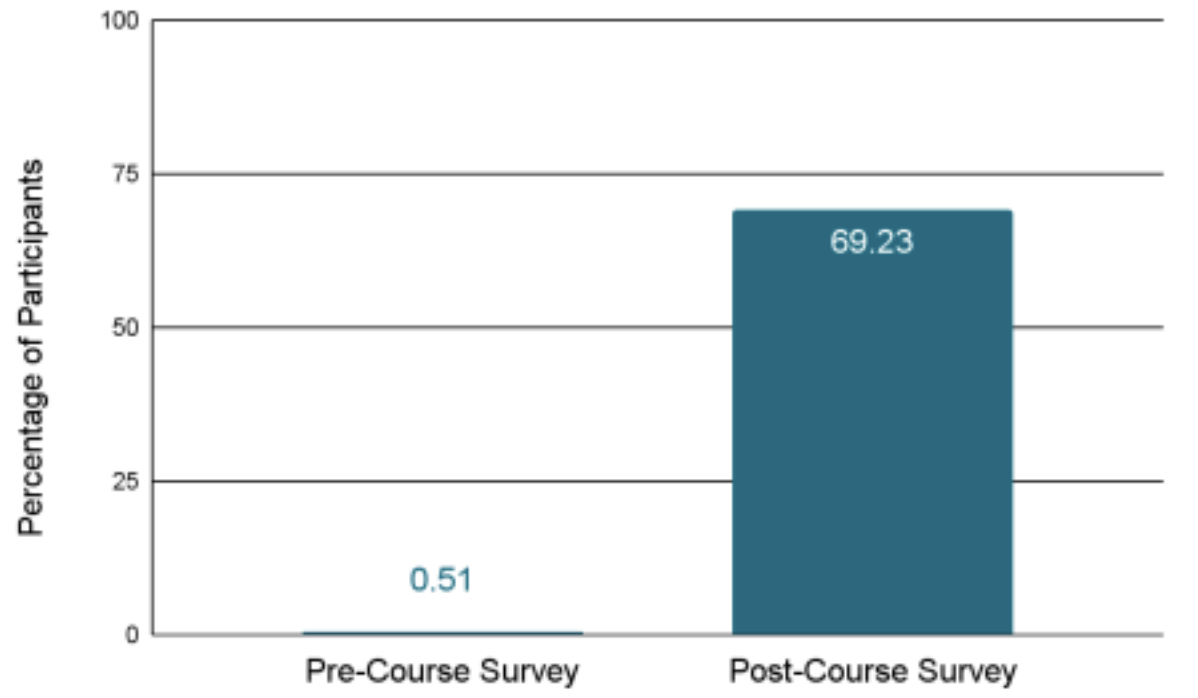

Before taking a Brainspring professional development course, 0.51% of teachers were extremely confident in their ability to implement the Orton-Gillingham structured literacy approach with students. After taking a Brainspring professional development course, this percentage increased to 69.23% (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Percentage of participants who responded “extremely confident.”

Note. The percentage difference of educators responding “extremely confident” on the Likert scale changed by 197.08%.

This study exemplifies how Brainspring provides educators with knowledge and confidence necessary to teach strong readers. Students of Brainspring-trained teachers are, therefore, better able to build the foundational literacy skills they need not just for education achievement but for lifelong health and well-being.

References

Alliance for Learning Innovation. (2024). Mississippi miracle. Alliance for Learning Innovation. https://www.alicoalition.org/mississippi

miracle#:~:text=When%20lawmakers%20passed%20Mississippi’s%20Literacy,reading %20assessment%20repeat%20third%20grade

Bozkuş, K. (2025). Predictors of reading performance of fourth-graders. European Journal of Education, 60(2), 1-13. 10.1111/ejed.70062

Coughlin, S. S., Vernon, M., Hatzigeorgiou, C., & George, V. (2020). Health literacy, social determinants of health, and disease prevention and control. Journal of Environment and Health Sciences, 6(1), 3061. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7889072/

DellaVecchia, G. P. (January 2020). Don’t leave us behind: Third-grade reading laws and unintended consequences. Michigan Reading Journal 52(2), 9.

https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2893&context=mrj Javorsky, K., Fondren, K., Mulkana, A., Smith, K. (2024, July). Effectiveness of early literacy policies when statewide efforts support them. Southern Regional Education Board. https://www.sreb.org/post/effectiveness-early-literacy-policies-when-statewide-efforts support-them

National Assessment of Educational Progress. (n.d.-a). NAEP report card: 2022 NAEP reading assessment. The Nation’s Report Card.

https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/highlights/reading/2022/

National Assessment of Educational Progress. (n.d.-b). NAEP Data Explorer. The Nation’s Report Card.

https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/profiles/stateprofile/overview/MS?cti=PgTab_OT&su b=MAT&chort=1&st=MN&sfj=NP&sj=MS

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.). High school graduation. Healthy People 2030. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants health/literature-summaries/high-school

graduation#:~:text=Individuals%20who%20do%20not%20graduate,self%2Dreport%20o verall%20poor%20health.&text=They%20also%20more%20frequently%20report,or%20 stomach%20ulcers%20—%20than%20graduates

O’Neill, G., & Geisler, P. (2023). Health literacy as a pathway to wellbeing: A celebration of health literacy month. Delaware Journal of Public Health, 9(5), 12.

https://doi.org/10.32481/djph.2023.12.004

Shahid, R., Shoker, M., Chu, L. M., Frehlick, R., Ward, H., & Pahwa, P. (2022). Impact of low health literacy on patients' health outcomes: A multicenter cohort study. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 1148. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08527-9

Shulman, K., Baicker, K., & Mayes, L. (2024). Reading for life-long health. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2024.1401739

Tolonen, H., Reinikainen, J., Koponen, P., Elonheimo, H., Palmieri, L., Tijhuis, M. J. (2021). Cross-national comparisons of health indicators require standardized definitions and common data sources. Arch Public Health, 79, 208. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-021- 00734-w

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2025, February 6). Health Literacy. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nih.gov/institutes-nih/nih-office-director/office communications-public-liaison/clear-communication/health-literacy

World Health Organization. (2024, August 5). Health Literacy. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/health-literacy