Beef-Up Your Blending: Blending Techniques for Stuck Students

Posted by Brainspring on 5th Aug 2020

After children have learned a few single consonant letter-sound correspondences and at least one vowel, they are ready to read some simple words. Think about it… How many CVC words can be made using the Starting 7 letter/sound correspondences (o, a, d, g, c, t, m) introduced in the first Seven lessons in Phonics First? Really, quite a few.

Students should begin putting letters/sounds into meaningful words as soon as they can, starting blending drills as early as possible! When teaching students to decode, we should begin with single consonants and short vowel sounds, because those are the sounds they are learning when they are learning the alphabet. This sets the foundation for decoding more advanced patterns in multisyllabic words.

When working with a student during a blending drill, you may find this scenario common:

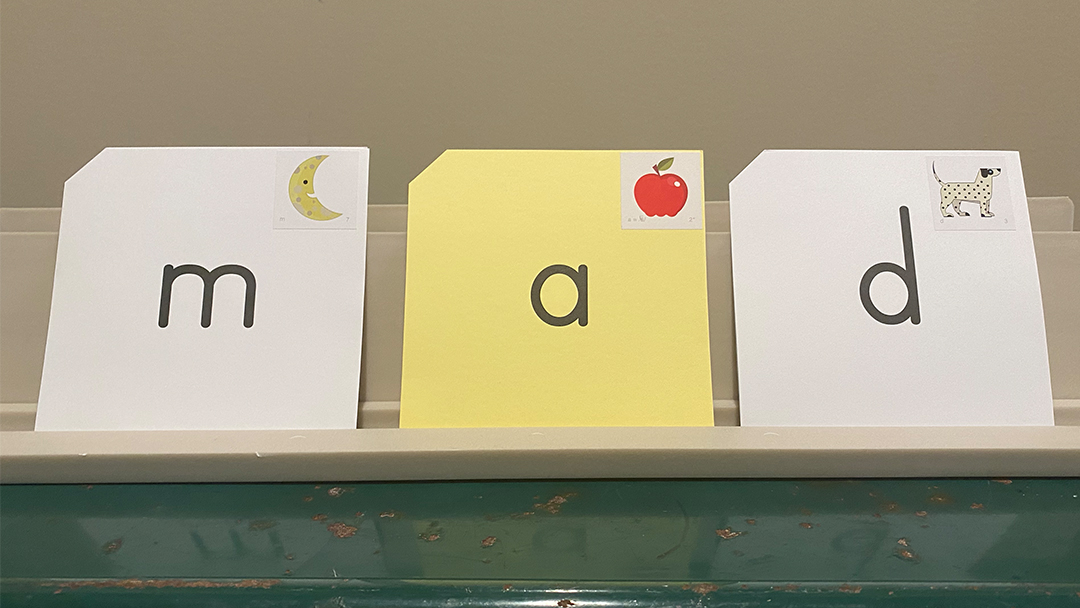

Teacher: (placing the letters “m” “a” and “d” on a blending board)

“Emily, say these sounds and blend together. Ready…read.”

Emily: “/m/…/a/… /d/” “dot”

What? How did she get “dot” from /m/ /a/ /d/? Actually, it’s pretty common for our beginning readers to correctly say each sound and then come up with a totally incorrect word. So, why is this?

A big part of this has to do with short term memory. When we are asking our students to decode a CVC word, we are asking them to first recall the phonemes, or sounds for these three letters, and then hold those individual sounds in their memory before going back to blend the sounds together in the correct sequence represented. So not only are we asking them to blend, we are asking them to remember each phoneme in the correct sequence. It is difficult for some students to make the connection between a seemingly random string of phonemes (sounds) and an actual word.

In the above blending scenario with Emily, she was able to identify the individual sounds as /m/…/a/…/d/. However, because Emily views these sounds as random, she is relying completely on her working memory to recall the sounds in sequence. In the above scenario, Emily produced a word that began with the final sound she recalled. Other students may produce words with additional sounds /mats/ or sounds out of sequence /dam/. Because these sounds initially appear random, reproducing the sounds in sequence taxes short term memory.

In the book, Making Sense of Phonics: The Hows and Whys by Isabel Beck, she outlines a strategy called Successive Blending, that will help children to apply blending independently. When using successive blending, children say the first two sounds in a word and immediately blend those two sounds together. Then, they say the third sound and immediately blend that sound with the first two blended sounds. Therefore, Successive Blending is less taxing on short term memory.

Beck’s 8-Step Sequence for Blending

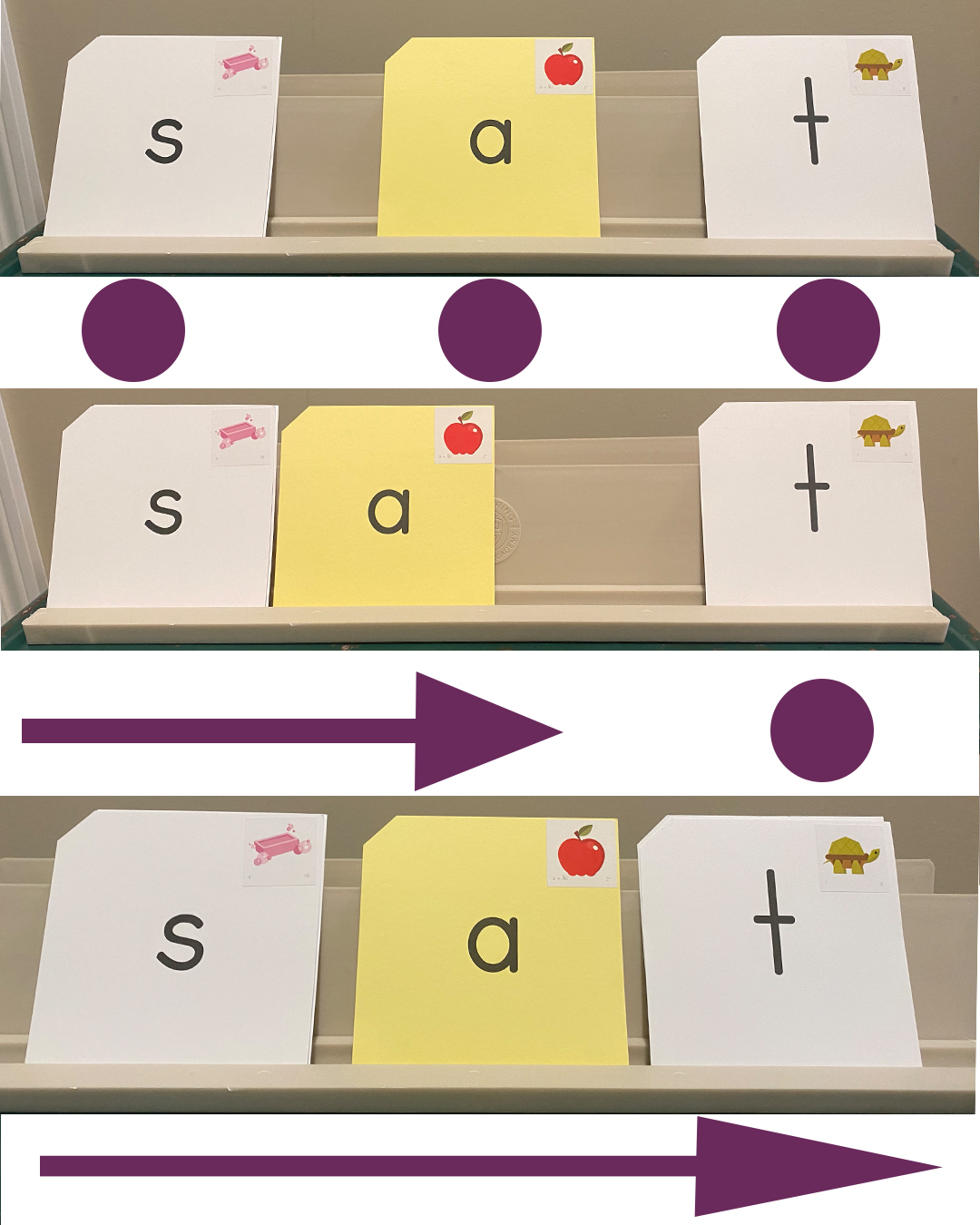

Place the letter cards “s” “a” and “t” separated on a blending board.

Place the letter cards “s” “a” and “t” separated on a blending board.

- Point to the “s” and say /s/

- Point to the “a” and say /a/

- Physically slide the “a” over to the “s”

- Slide finger along the “sa” and say /sa/

- Point to the “t” and say /t/

- Move the “t” card next to the “sa” to make the word “sat”

- Slide finger under “sat” and say “sat” slowly

- Read the word naturally and indicate that the word is “sat”

Consider what successive blending would look like if you are using initial consonant blends.

/f/ /l/ … /fl/ … /a/ … /fla/ … /sh/ /flash/

Practicing the blends as separate sounds, initially, will discourage students from slipping in that ‘extra’ vowel sound in between the consonant blend sounds. For example, “/flash/ may be blended as /fulash/ or /ful/ /ash/. Once students recall blends as correct sound units, they can unitize these sounds correctly…/fl/ /a/…/fla/…/sh/…/flash/.

Children use this strategy only to the point that they need to. Once students can independently engage in the steps of blending a new word, there is no need for them to continue to blend overtly. Blending is a little like saying, “A little salt on my French fries is tasty, but too much is unhealthy.” Once students can demonstrate they know the blending procedure, it is time to remove the scaffold of successive blending and begin tapping/blending three sounds. Some may need to remain at the successive blending stage for quite a while. Sometimes it can seem as though these students may never progress beyond successive blending.

Blending is not an impossible skill to master. It simply requires practice and lots of it. It’s critical to introduce children to the phonemic awareness skills of oral blending at an early age. Modelling how to orally blend to create a spoken word and how to break a word apart is how to start a child’s blending and segmenting journey. Once children can blend at an oral level, the blending of words in print becomes a lot easier. It may feel like you are going backwards, especially, if the child is much older but this skill needs to be firmly embedded. It can feel like a real challenge for a teacher who has students who can’t blend ‘cat’ and also those who are reading chapter books! For these older students it’s often the same issues the beginning reader is having and must be intervened with at that same level.

Additional Blending Techniques

- Isolated blending– say the first sound the loudest and then get softer as you get to the end of the word. Children do tend to start blending with the loudest sound they heard. So, make sure your first sound is the loudest.

- Final blending– blend the first two letter sounds together and then snap it with the final letter sound. For example:

This helps with children who are not following through with their blending or with those who just cannot hear the spoken word being formed.

The expectation is that students will eventually recognize the words as units and find successive blending unnecessary. Remember, patience will pay off! Eventually the light bulb will click on! Blending just needs lots of modeling, repetition, practice, and a steadfast determination that every child will learn to read!

Additional Teaching Resources:

Written by Samantha Brooks, MSE, CDP.

Samantha is a Brainspring Instructor.

Brainspring has proudly supported the educational community for more than 25 years.

Our Educator Academy provides educators in grades K-12 with comprehensive MSL Professional Development courses. Learn more about our in-person and online professional development.

The Learning Centers support students through one-on-one, multisensory tutoring sessions. Learn more about our in-person (available in Southeast Michigan) and nationwide online tutoring.