Learning to Read: The Starting Point

Posted by Brainspring on 17th Mar 2021

[Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in March 2019.]

Today’s blog gives a quick glimpse into the astounding, yet complicated, way in which our brains first start learning to read. What a significant role we have as educators and parents in helping our students learn to read!

Good readers can…

- Recognize a word in 1/20th of a second.

- Read 150-250 words per minute.

- Immediately recognize tens of thousands of words.

- Learn new words very quickly.

~Equipped for Reading Success, David A. Kilpatrick, Ph.D

How do readers get to this point?

Humans are hard-wired for spoken language and have been using speech for around 100,000 years. There are areas of our brain specifically designed to process the sounds and grammar of whatever language we are exposed to at the beginning of our life. However, our brains have not been hardwired to understand written language. Reading is a skill that must be explicitly taught. There is a powerful connection between the words and sequence of sounds we are exposed to early in life and the ease in which our brains are able to learn to read.

Word meaning is activated based on what we hear.

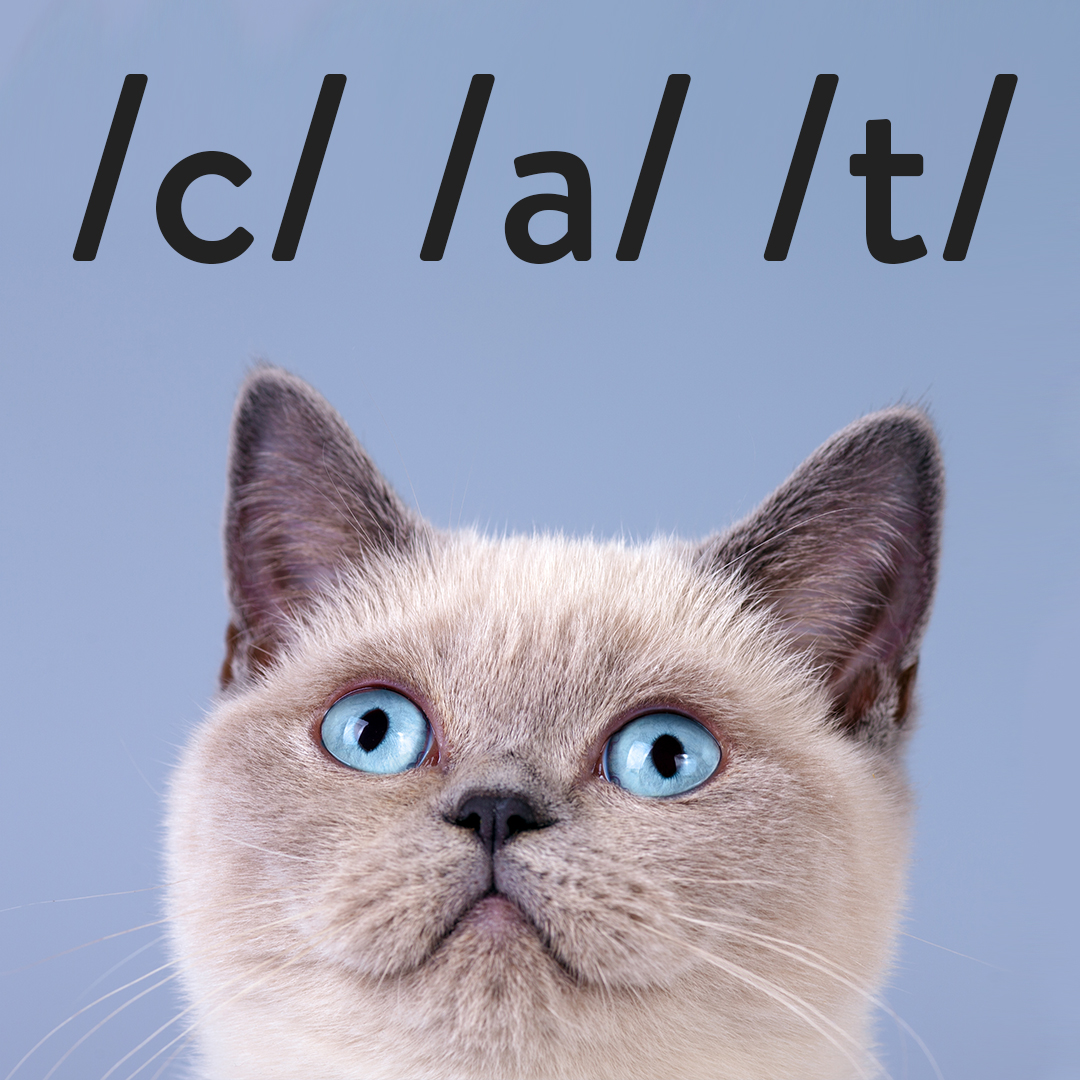

For example, a teacher says the word “cat” to his students. The students hear a sequence of sounds (/c/ /a/ /t/), the sound sequences are recognized and matched to stored sounds in the brain, oral vocabulary is activated, then the meaning is retrieved.

Imagine all of the words we have heard up until now. Those words are stored in a sort of “filing cabinet” in our brain that allows us to instantly access the words when needed. The sequence of sounds in each of these words are activated in our oral and mental dictionaries (making speaking super convenient).

What happens when speech is unfamiliar to us? Imagine you are listening to a foreign language. If, for example, you are not familiar with the French language and hear someone say the phrase below…

…the sequence of sounds you hear is essentially meaningless because they do not match any of the sequence of syllables in your mental dictionary (ie they have not been previously introduced/repeated).

The foundation for reading words is built on this sort of “filing system”. If we want our students to become fluent in reading, we must understand that words are not stored in this filing system via visual memory. Words are stored auditorily, or phonologically.

![]() An analogy…when you bring groceries home, you bring them through the front door (or input them) but store them in a different spot such as the fridge/pantry/cabinets.

An analogy…when you bring groceries home, you bring them through the front door (or input them) but store them in a different spot such as the fridge/pantry/cabinets.

When reading, words are input visually and stored auditorily (phonologically). Written words can be anchored into permanent memory if the reader is able to identify a meaningful string of sounds that also match the spoken word.

“Letter sequences in words are meaningful because the letter order is designed to match the order of the sounds in spoken words” (Kilpatrick, 2016).

![]() For example, if we were to play a memory game and give educators and non-educators the following letter strings, who do you think will be more likely to recall the letter strings?

For example, if we were to play a memory game and give educators and non-educators the following letter strings, who do you think will be more likely to recall the letter strings?

* ADD IEP LD ESL PTA SPED

The teachers, of course! These are familiar because as educators, we hear, say and see them all the time. We have mapped them in our “filing cabinet” and they are anchored in. Non-educators will have to practice more to become automatic in recalling their meaning.

How Do We Map?

We now see that familiar strings of sounds and letters become mapped in our brain, stored for immediate and future use. But how do we map these sounds to letters?

We must visually memorize the letters of the alphabet and the sounds each of these letters make to know what each of the sounds are in a word. Then, once strings of letters are familiar, they can then become treated as a unit.

To keep this simple – think exposure. In the early grades/years, students should be exposed to letters and sounds constantly. This will help ensure that the letter-sound associations are anchored in their brain. Kilpatrick states “when they become automatic, the sight of the letter will activate the sound in memory just as quickly and efficiently as if the student heard someone produce the sound orally.”

As letters, sounds and phoneme awareness become stronger, students begin to see strings of letters unitize, or become more of a unit. Think of the letters/sounds /at/. There are many words that contain /at/ such as cat, mat, sat, bat, fat, pat, etc. Once the student has practiced words with /at/ over and over, the unit has been filed away in her oral dictionary. If, however, the student does not have strong phoneme awareness, this string of letters does not have anything to anchor itself to in memory. The sound string, therefore, has to be memorized, which is not efficient. Once phoneme awareness is strong, the student can make the connection between the sound and symbol.

Think – printed letters piggyback onto the phonemes/sounds in our filing system. Without first knowing the sound, the print will have a hard time anchoring and thus forming a sound- symbol connection.

So what about students who struggle with this process of learning to read?

It is estimated that individuals with learning disabilities may have to review a skill 50-100 times until mastery is demonstrated. This is where explicit, multisensory phonological awareness and phonics comes in. Programs that are Orton-Gillingham based use multisensory instruction that starts from the ground up. Each time sounds/skills are introduced, students are using multisensory approaches to “lock in” the sounds/skills. There is also plenty of repetition and review, which ensures the student does not move on until they are demonstrating more automaticity in the previously learned material.

We very briefly skimmed the surface in this article on the beginning steps of the science of teaching reading. If interested in learning more, we would recommend checking out the book referenced in this article Equipped for Reading Success, David A. Kilpatrick, Ph.D, which you can find here.

If you would like further information on phonological/phonemic awareness, check out a couple of our previous articles on the subject:

The Roots to Reading and Spelling

The Difference Between Phonological and Phonemic Awareness

Brainspring has proudly supported the educational community for more than 25 years.

Our Educator Academy provides educators in grades K-12 with comprehensive MSL Professional Development courses. Learn more about our in-person and online professional development.

The Learning Centers support students through one-on-one, multisensory tutoring sessions. Learn more about our in-person (available in Southeast Michigan) and nationwide online tutoring.