Dysgraphia: A Multisensory Approach to Handwriting Struggles

Posted by Guest Blogger on 15th Jan 2020

Being able to write accurately and fluently is very important in written expression. Dysgraphia, a specific learning disability of written expression, is often discovered through a student’s written work. Dysgraphia is defined as a learning disability that affects handwriting. Students with dysgraphia often struggle with spacing, letter formation, and spelling—even when they have great ideas.

Be Alert for the Signs of Dysgraphia

Recognizing the signs of dysgraphia early can help students get the support they need to improve their writing fluency and confidence. Dysgraphia doesn’t always look the same in every child, but these common signs may indicate a struggle with spatial awareness and motor planning:

- Inconsistent letter sizing – Tall and short letters may be the same height, or letters may float above or below the line.

- Poor spacing – Words and letters may run together or appear unevenly spaced.

- Heavy pencil pressure – Some letters are darker or “etched” into the page, while others are faint.

- Unusual letter formation – Letters may be formed incorrectly or with extra strokes.

- Incorrect capitalization – Capital letters may be used in the middle of words without reason.

- Misspelled words – Even when a child can spell the word aloud, it may appear jumbled or incorrect in writing.

- Difficulty copying from the board or a book – Students may skip lines or lose their place easily.

- Avoidance of writing tasks – Reluctance to write, frequent complaints of hand pain, or rushing through assignments may be signs of frustration.

Handwriting Analysis

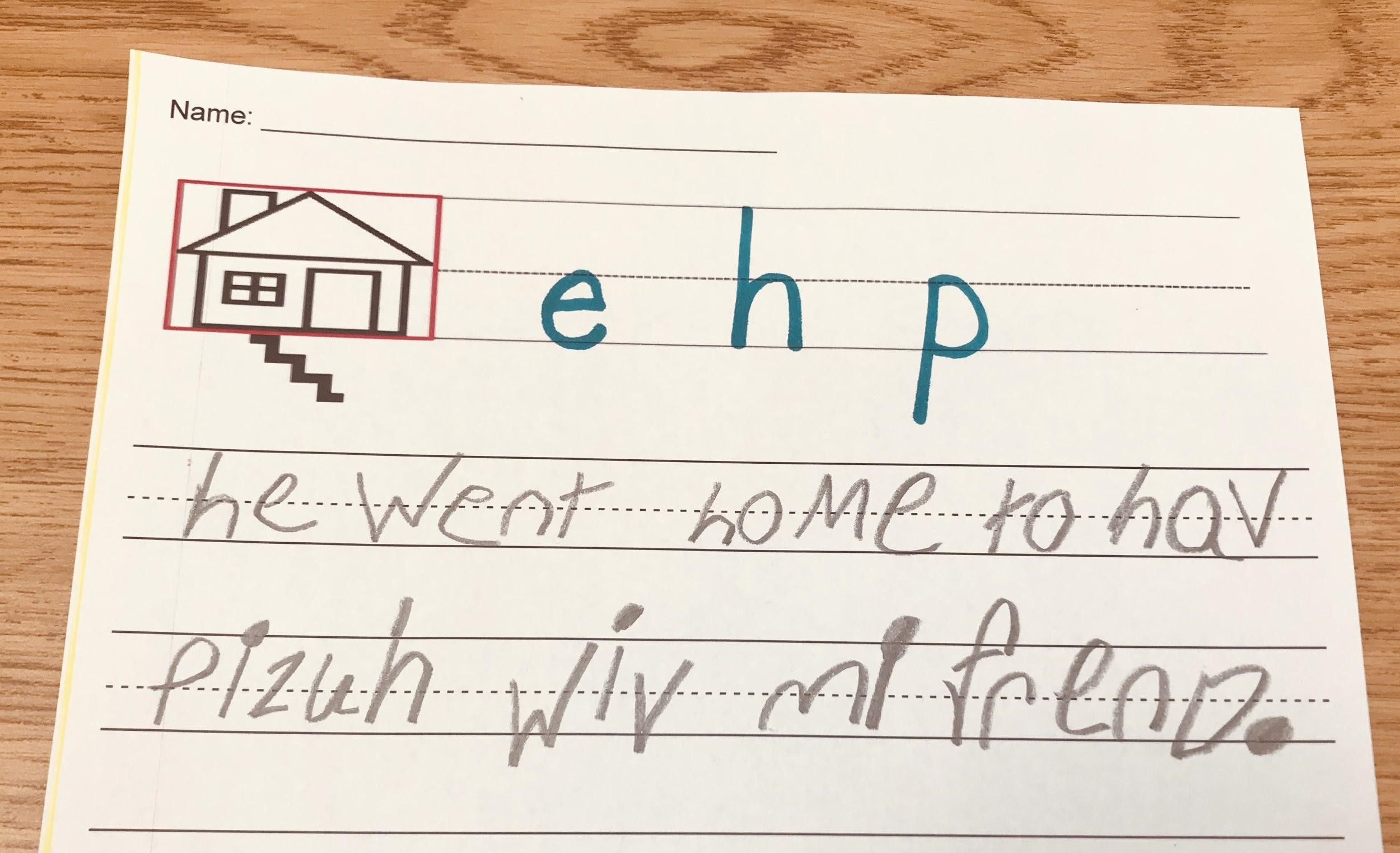

One of the quickest ways to identify potential writing struggles is to study a student’s handwriting. Below is a writing sample from a student with dysgraphia—with errors in both handwriting and spelling:

Errors:

- Incorrect or unnecessary capitalization (h, D, M)

- Small letters (e, n, o, a, v, i, z, u) are above the dotted line (ceiling) or appear to be floating

- Misspellings (hav, pizuh, wiv, mi, frend)

- Tall letters are not sized to other lower case letters (in the misspelled word of hav[e], the size of the “h” is similar in size to the “a” and “v”)

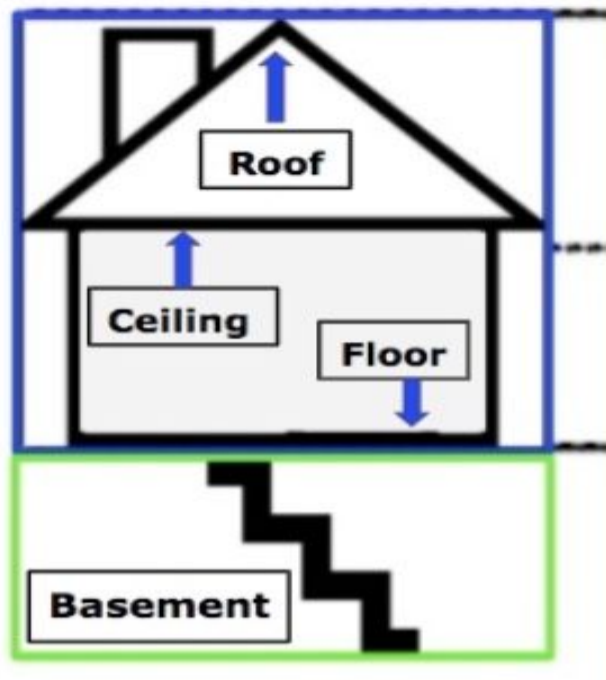

- The tailed letter “p” is not dangling into the basement (see the below house diagram)

- The dotted “i” is either attached, looking more like a lollipop, or is not proportionally sized

- Some letters, including the period, appear to be written in a darker pencil

- Letter formation (f, n) is incorrect

The good news is by using a consistent, multisensory approach in letter formation, students can learn how to motor plan properly which can certainly decrease the visual evidence found in dysgraphia and improve writing fluency.

Using these concrete references: roof, ceiling, floor, and basement, will allow students to spatially plan where letters belong. When learning how to write a new letter, it is very important to speak this terminology aloud. This is also part of the multisensory experience.

Dysgraphia Handwriting Exercise: Going from Big to Small

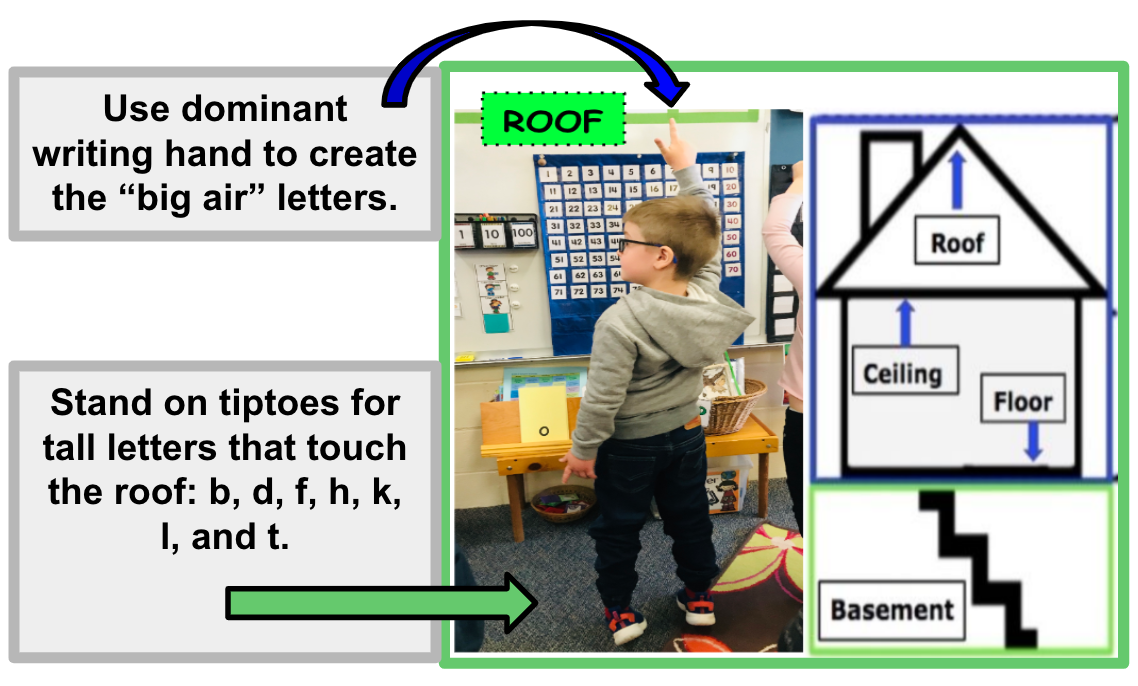

In the younger grades, I have students “big air” write the letter (3 times) before practicing it on house paper and then in the sand. This “air writing” improves gross motor skills and also provides more practice in “crossing the midline”.

As always, I first model the new letter, using the house terminology. For a tall letter, such as l, I would say “I am going to stand on my tiptoes to start my letter at the roof, then, down through the ceiling, and stop at the floor. For tailed letters, you might make your voice very deep when you say that the tail drops “down into the basement”. Students also kneel down and have the tail “touch” the actual floor.

Why This Multisensory Approach Works

Multisensory instruction helps students with dysgraphia and other spatial challenges form stronger neural pathways for learning. Instead of relying on a single method like a visual worksheets alone, the multisensory approach combines sight, sound, movement, and touch to reinforce correct letter formation.

Visual learners benefit from seeing demonstrations and color-coded visuals like house paper. Auditory learners absorb verbal cues and the repetition of letter formation steps. Kinesthetic learners strengthen memory through gross motor movement, like air writing, and fine motor tasks like sand writing or pencil work. These strategies all support motor planning, spatial awareness, and letter memory. By engaging multiple senses at once, students are more likely to retain and apply what they’ve learned.

What You Can Do at Home or in the Classroom

Parents and teachers don’t need specialized tools to help support students with dysgraphia. Here are some simple, effective ways to support students with spatial and writing challenges using a multisensory approach:

At Home:

- Print or draw house paper and use it for all handwriting practice.

- Encourage air writing while standing or kneeling for multisensory engagement.

- Fill a tray with salt, sand, or rice for writing activities.

- Use sidewalk chalk outside for large letter practice with movement.

In the Classroom:

- Begin handwriting sessions with a modeling + air writing routine.

- Use verbal cues consistently across classrooms

- Pair students with a visual of the house paper zones for reference.

- Offer alternative writing tools like larger pencils, pencil grips, or slanted boards to support fine motor control.

No matter the setting, consistency and encouragement go a long way. Helping a student feel successful and seen in their writing journey builds skills and confidence.

References

How to Spot Dyslexia: In a Writing Sample

Dysgraphia: What You Need To Know

Written by Jennifer L. Padgett, M. Ed.

Jennifer is a Literacy Specialist, K-12

Mexico, Maine